This year marks the 150th anniversary of a remarkable event that occurred here in Richmond. Now, this last day of 2015 affords me a final opportunity to commemorate the anniversary and atone for my procrastination. The event was simply the ascension of a balloon carrying five passengers. The remarkable aspects of the event arise from the circumstances of the voyage and the ensuing adventure of the passengers – an adventure so fantastic, so incredible that the world can only regard it as fiction.

These exploits were dramatized by Jules Verne in his L'Île mystérieuse (first published in 1874). I use the word “dramatized” because Verne was more interested in telling a story instead of relating a factual account. As is often the case in his works, Verne sacrificed accuracy for the sake of literary style. Not that I blame him; if the final result would be labeled as fiction regardless, he might as well “improve” the story. Of course, Verne was not responsible for all deviations from the truth; some changes were necessary for legal reasons and others were imposed by editors.

The balloon passengers were Cyrus Harding Smith, Captain of the Union Army, and his associates – Gideon Spillet, Boniface Pencross, Herbert Dunn, and the “servant,” Neb. Please note that personal names were not immune to alteration in Verne’s narrative. Verne also added a dog. Anyway, in March of 1865, Captain Smith and company appropriated a military balloon to escape from Richmond. Due to inclement weather, they had no practical control of the balloon. As a result, they eventually arrive at a mysterious island. Here we see a profound departure from reality on Verne’s part. Verne’s description of the weather is thus:

Few can possibly have forgotten the terrible storm from the northeast, in the middle of the equinox of that year. The tempest raged without intermission from the 18th to the 26th of March. Its ravages were terrible in America, Europe, and Asia, covering a distance of eighteen hundred miles, and extending obliquely to the equator from the thirty-fifth north parallel to the fortieth south parallel. Towns were overthrown, forests uprooted, coasts devastated by the mountains of water which were precipitated on them, vessels cast on the shore, which the published accounts numbered by hundreds, whole districts leveled by waterspouts which destroyed everything they passed over, several thousand people crushed on land or drowned at sea; such were the traces of its fury, left by this devastating tempest.In essence, Verne presents a phenomenal storm that lasts more than week, afflicts three continents, and causes inestimable property damage. This is a case of exaggeration. In reality, the weather was not quite so dramatic. Regarding March 1865, Robert K. Krick provides the following information in his Civil War Weather in Virginia :

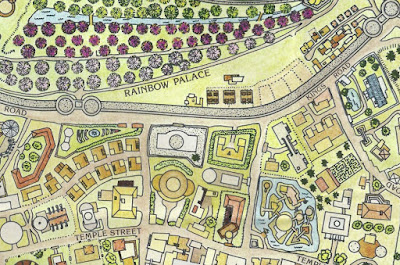

Richmond’s residents saw a “splendid rainbow” on the night of March 15. The next night “a violent southeast gale prevailed . . . with rain.” Bright sun tempered winds still blowing through Richmond on the 18th, but the dawn of the 19th reminded a diarist of spring in the Garden of Eden. Warm and pleasant weather continued into the 21st, when blossoms appeared on apricot trees.I had not realized that former residents of Eden were living in Richmond during the Civil War. Perhaps the phrase “reminded . . . of” was meant to convey “inspired notions . . . of” rather than an actual recollection. Regardless, Captain Smith and his companions likely ascended on the night of March 16 when there was a “southeast gale.” In Verne’s version, the party leaves on March 20 and the storm is “from the northeast.” Verne’s “aerial maelstrom” carries the balloon thousands of miles contrary to the jet stream in about seventy-two hours. Verne must invoke such a preposterous storm because he chose to place the Mysterious Island in the Pacific. I suppose there are many mysterious islands in the Pacific, but the Mysterious Island – the one where Captain Smith’s party found themselves – is in the Atlantic. So why the switch in ocean? I can’t answer for Verne, but I suspect the explanation (or at least a partial explanation) is that divulging factual information about something mysterious would tend to compromise the mysterious nature of said something. Mysterious Island is mysterious for a reason and – to this day – the ‘powers-that-be’ have a vested interest in that reason and in maintaining the mystery.

You won’t find Mysterious Island via Google Earth. Very few maps chart the island’s position and those that do are secreted in secure collections to which the public is not admitted. A flat-out denial of the existence of Mysterious Island is not feasible, but it is easy enough to suggest that any given reference to it stems from fiction; thereby, the mystery is preserved. I believe Mysterious Island’s official status (perhaps ‘official non-status’ is more apt) can be traced to an amendment to the Treaty of Tordesillas. However, the only surviving copy of that amendment is in the Vatican’s Secret Archives; not the Secret Archives that everyone knows about, but the really Secret Archives. Rumors that pre-human artifacts were found on the island (and that the Church wanted that knowledge suppressed) are unsubstantiated (yet not entirely disproved).

Eventually, Captain Smith and the others encounter Prince Dakkar (more commonly known as “Captain Nemo”), one of the most misunderstood figures of the 19th Century. (Verne manages to depict him as both a misanthrope and a humanitarian.) Once again, Verne’s account veers away from the actual circumstances.

The events of Verne’s Vingt mille lieues sous les mers (published in 1870 but serialized starting in 1869) transpire after the Civil War. When the story begins, the world is not yet acquainted with Prince Dakkar’s depredations. However, in L'Île mystérieuse, the exploits of Prince Dakkar are well-known to Captain Smith and company even though they have been on the island since the conclusion of the war, ignorant of any subsequent world events. In terms of storytelling, Verne didn’t want to weigh down the narrative with exposition from his earlier work. Since the readers knew about Captain Nemo, then so should the protagonists.

In truth, Vingt mille lieues sous les mers (hereinafter Leagues) follows L'Île mystérieuse, not vice versa. It was Gideon Spillet who ‘broke the news’ about Prince Dakkar to an astonished world. Spillet accompanied Prince Dakkar during the events of Leagues and, since he was a journalist, he reported those events. Verne’s account is narrated from the point-of-view of his long-time friend Pierre Aronnax. No mention was made of Spillet in Leagues due to a dispute over publication rights. Spillet and Verne reconciled their differences by the time the latter wrote L'Île mystérieuse, so Spillet appears in that story. Shortly after their reconcilement, Spillet met an untimely death. However, Verne could not include Spillet in updated editions of Leagues because of complications with Spillet’s estate. Those complications also prompted Verne to change the spelling of Gideon Spillet to the unabashedly French Gédeon Spilett. American editions used the ‘Gideon’ spelling.

Prior to Prince Dakkar’s claim to the island, it had been used sporadically as a refuge for pirates (or, alternatively, a staging area for privateer activity). In any event, I consider theories that conflate ‘Treasure Island’ with ‘Mysterious Island’ to be altogether fanciful.

The destruction of Mysterious Island in a fit of apoplectic volcanism is another of Verne’s inventions. I guess it makes for a good story. (SPOILER: The dog survives!) In reality, the island fared just as it had previously – largely unknown but occasionally called into some peculiar service.

During the Second World War, Mysterious Island was used as a base of operations by the Blackhawk Squadron. This multi-national task force employed cutting-edge aviation technology against Axis threats, often of an outré variety. During this time, Mysterious Island was known as Blackhawk Island. Notwithstanding the legend of their comic book analogues, the Blackhawks disbanded shortly after the war. Allegedly, this was done at Stalin’s insistence and was a source of contention at the Potsdam Conference.

Eventually, a colony was established on Mysterious Island. Specifically, it was an involuntary retirement community for people possessing knowledge inimical to the status quo. Whether the island still hosts this colony is a matter of conjecture. When inquiring about some things – such as the particulars of Mysterious Island – prudence should be exercised. After all, questions are a burden to others; answers a prison for oneself.